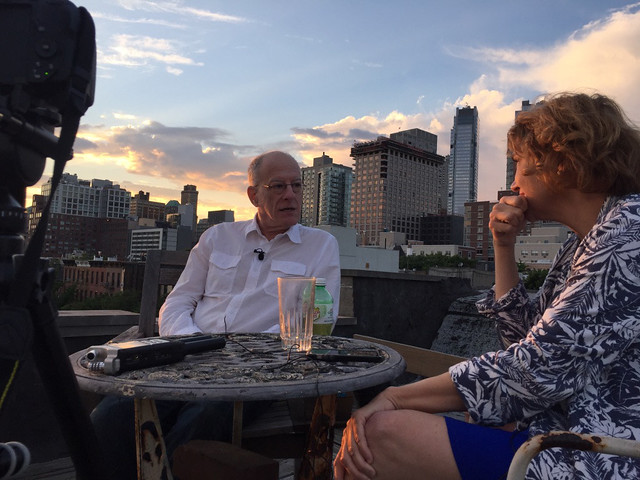

In January 2017, I came to the Washington DC area to investigate the representation of Islam and Muslims in higher education, Islam on campus for short. George Mason University (GMU) was my case study for my Fulbright-Schuman research project. The rationale for choosing GMU was because the university is one of the most ethnically diverse in the country. In particular, 18.2% of students are from an Asian background. The Fairfax campus, the hub of undergraduate student life, welcomes a large commuter population. Some of these commuters are students of South Asian background who identify as Muslims, although precise numbers are hard to come by. What is clear, however, is that the Fairfax area has a vibrant Muslim community. So, at Mason, Muslim students don’t feel like a minority: they feel at home.

At Fairfax, the sound and fury that has characterised the Trump presidency is barely noticeable. Of course, there was considerable upset regarding the travel ban issued by Donald Trump on the 27th of January 2017. However, only one GMU student was affected. Najwa Elyazgi was prevented from coming back from Libya after the travel ban. Her ordeal lasted a week, after which she was allowed to renter the United States. Since then, the controversy has died down. It looks as if the revised travel ban would have no impact on foreign students or staff coming from the countries under scrutiny, since an invitation to work or study at an university would qualify as a bona fides relationship with the US. If anything, in January/February 2017, Muslim students were pleasantly surprised by the strong, spontaneous reaction of solidarity emanating from various quarters of American civil society.

GMU is a very peaceful campus. It’s certainly not a hotbed of student activism, even though it’s not apolitical. The other big public research university in the Washington DC area, the University of Maryland, has a much more explicit tradition of student activism han GMU, both on the left as well as the right. Tragically, on 20 May 2017, a black student Richard Collins, was stabbed to death by a white student at the University of Maryland. So far GMU seems to have been spared such incidents.

Throughout my six-month stay, I interviewed several Muslim students from various backgrounds. Many were of South Asian origin, but others were African Americans or whites. Many of my interviewees were members of the Muslim Student Association (MSA). The majority felt their faith was a very important component of their life and their identity. They demanded respect for their religion and were keen to challenge anti-Muslim stereotypes, mainly associated with terrorism as a result of negative coverage on all things Islam in the mainstream media.

They said they rarely encountered any manifestation of bigotry on campus. In fact, the interviewees were generally happy with the level of support offered by GMU with respect to the accommodation of religious needs. Indeed, the university has made tremendous efforts to provide an environment where Muslims can practise their faith. In particular, quiet meditation spaces on campus enable Muslim students to pray in a dedicated area instead of ‘hiding’ under a staircase. Foot wash facilities have also been installed in two bathrooms near the meditation space. Although it’s open to everyone, the space tends to be mostly used by Muslim students. That’s why there are regular complaints that the University de facto sponsors the Islamic faith, thus violating the first Amendment of the US Constitution, which prohibits Congress from preferring or elevating one religion over another. But these complaints have for the most part fallen on deaf ears, because the space is explicitly dedicated to meditation, not prayer.

Two respondents reported incidents of micro-aggression by professors or on social media, but such incidents are difficult to prove. The Office of Ethics and Compliance said that although Muslim students have complained about Islamophobia on campus, it was more a subjective feeling than anything concrete. This did not mean that the university was not taking these complaints seriously. The Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Multicultural Education (ODIME) has been proposing courses to help staff to become more aware of cultural and religious diversity. The Campus Climate Group also closely monitors the atmosphere on campus, even though senior management staff and professors alike said they could never be aware of everything that happens on campus.

On the whole, campus relations seemed to be quite harmonious at GMU, with no obvious tensions between various parts of the student body. Part of the reason for this state of affairs could be that there’s been no overlap between pro-Palestinian, anti-Israel activism and the MSA. The MSA at GMU functions as a congregation that helps Muslim students develop a sense of belonging, solidarity and mutual understanding. The leadership is trying to promote a positive image of Islam as a tolerant and open faith in phase with American constitutional values. It is even hoped that by promoting an open, diverse and pluralistic interpretation of Islam, more young people will be interested in joining or rejoining the faith. This effort is particularly directed at young people of Muslim culture, mainly in the Fairfax Northern Virginia area. That’s why there is no peer pressure to wear the hijab, for instance. Quite the opposite: MSA leaders explain that no one will be judged on how they practice their faith at MSA social events.

It is a fascinating time to be researching the representation of Islam in higher education in Europe and the United States. I feel privileged to have gained some insight into how American Muslim students live in the age of Trump, how they challenge negative stereotypes concerning their faith while never giving the impression that they are feeling under siege. I was also on the whole impressed by how senior management try to accommodate the expression of religious identity on campus in ways that would be unthinkable in some European countries. American academia has embraced a diversity-oriented, pluralist ethos that is supported by strong organisational resources. Thinking of the European context, training in diversity could certainly help dissipate misunderstandings that more often than not arise from sheer ignorance, the mother of all forms of racist prejudice.

I am grateful to all my interviewees for opening up to me and talking to me about their experiences as administrators, professors and students. This experience has helped me challenge my own views about the place of religious identity in higher education today. Thanks to the Fulbright-Schuman programme, I have improved my research skills, gone out of my comfort zone and formed new transatlantic friendships. I hope this dialogue will continue.

–

Dr. Anne Daguerre,

2016-2017 Fulbright-Schuman grantee