“This might sound strange, but for me, work has been a type of spiritual adventure.” Paul Nihou, a Judge at the General Court of the European Union, was reflecting on his career to a group of Fulbright scholars and students at a recent visit to the European Court of Justice, and it resonated with me as I’ve thought about my own experiences so far this year.

As a Fulbright-Schuman Award recipient, my project this year is examining how undocumented migrants access healthcare in Spain and Italy. Similar to Judge Nihou’s comments, my project has unexpectedly brought up a lot of deeper questions about my own relationship with my faith and work.

I have always been a “doer.” Whether it was advocating for children in a South African township who had lost their schoolbus services, suturing lacerations of a woman who had just given birth in the middle of the night without electricity in a rural hospital in Eritrea, or driving a patient home after a shift in the ER in San Francisco, I’ve always felt like only one’s actions mattered. As a little kid, I remember sketching out my Saturdays, starting at the top of the page and drawing out a line for each hour to plan my day, trying to fit as many activities as I could into one day. And this natural predilection towards doing has without question been reinforced by our equally and, sometimes brutally, outcomes-oriented world.

Yet as I’ve operated in this mode my entire life, I’ve realized it’s easy to become too focused on the outcome (part of me still screams, “How can you possibly be too focused on the outcome? Isn’t that all that matters?”), and the impetus behind the actions gets lost along the way. As written by David Jenson in Responsive Labor: A Theology of Work: “Throughout history, humanity – and the church – have fallen captive to the idea that in work we create ourselves.” Over time, I have seen that perhaps some of my motivations stem from a desperate desire to prove my worth.

A natural consequence of this misdirected focus has been a neglect of the state of my heart. When I was younger, I remember learning about the idea of Imago Dei, the idea that humans are created in the image of God. I felt like it was a fluffy and irrelevant concept at the time, as if believing in it or not wouldn’t make any material difference in one’s life. But now I’ve seen that if I truly believe in that idea, it radically changes the way I see the person sitting on the street with a sign asking for help. It radically changes the way I see the undocumented migrant on the beach trying to sell wooden trinkets to me or my family. It radically changes the way I even approach thinking about my project.

If I am to be honest, over the past decade, my actions have been so focused on outcomes and productivity that I have lost sight of cultivating an alignment between my motivations and my actions. Many years ago, someone pointed out that in the Bible, Jesus’ main posture to seeing the suffering of people he encounters is compassion. I never noticed it before; to me, his his actions of healing people and doing miracles seemed much more interesting. But in fact, the idea that God desires compassion over sacrifice is echoed several times throughout the Old and New Testament.

While the word “compassion” often conjures up an idea of pity with perhaps even a trace of condescension, the Latin etymology of the word “compati” connotes the idea of suffering with others. And I realize it’s much easier to give a handout than to really share in someone’s suffering. Yet that is what I think I have been missing often in my work.

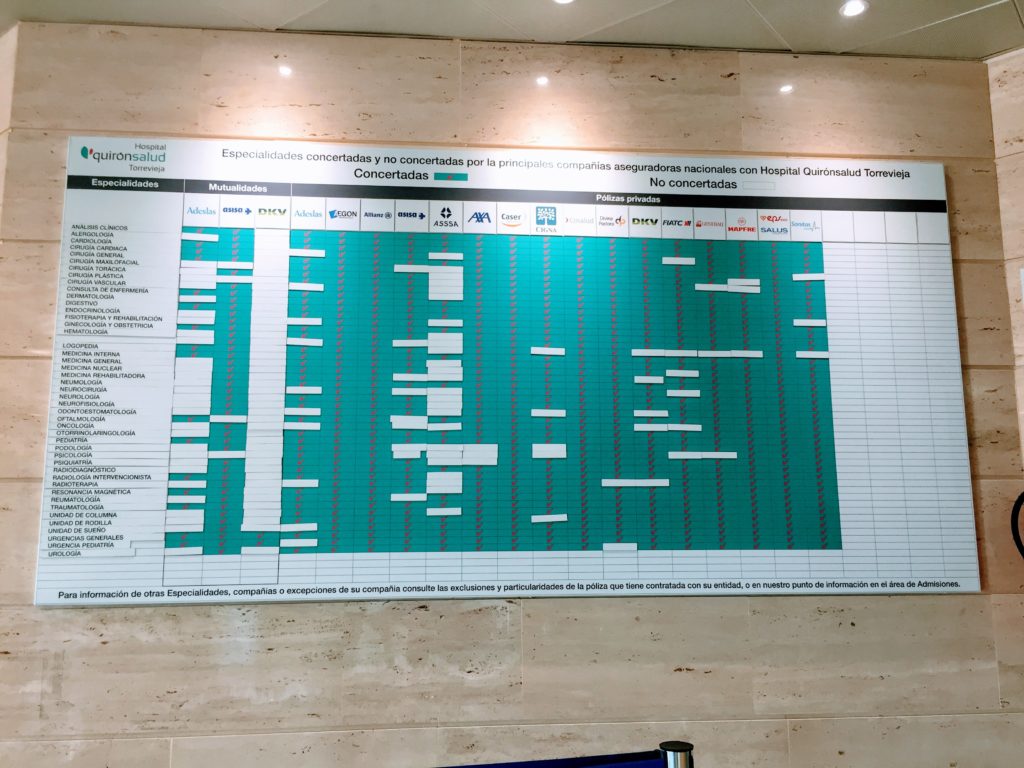

For me, compassion isn’t just a binary switch that can be turned “on” for the rest of my life. I am starting to understand that it requires an intentional practice of trying to identify with others who are created in the image of God but are in different circumstances. And while I will never truly understand the experience of an undocumented person seeking healthcare, I’ve had just the tiniest taste of what it might start to feel like. For example, the six-month process of getting our family visas to Spain was incredibly nerve-wracking for me, and that’s as a legal citizen of the United States with the backing of the Fulbright Commission. I cannot even imagine what it is like for someone who cannot understand the language and does not have any education or resources, much less the time or mental bandwidth, who may be trying to flee a dangerous situation. Or feeling incredibly vulnerable when I had just moved to Spain and began to experience some health problems and needed to navigate the healthcare and insurance system (the picture is one example of which insurance companies at this hospital provide specialty services – complex enough for those who are insured, and infinitely more obscure for those who are undocumented). And that’s with me being a physician, having purchased private health insurance, and knowing how to speak the language. Or even the time I was walking home in our relatively safe neighborhood in Spain around 11:30pm after accompanying our neighborhood babysitter back, and 2 young men started following me on the street. I had caught a cold and had laryngitis, and realized I literally had no voice to scream if I needed help. And yet that is exactly the situation that undocumented people likely feel all the time – that they have no voice.

While I can give facts about how undocumented migrants use fewer healthcare resources that their native-born counterparts, or provide persuasive philosophical perspectives on why we should care, and even practical economic arguments for the provision of healthcare to undocumented migrants, ultimately I am most grateful to the Fulbright-Schuman program for allowing me this opportunity to re-form the basis of what, how, and why I work. Ultimately, as musician Rich Mullins once said, we are called first to be lovers, not saviors.

As a recipient of a 2019-2020 Fulbright Schuman European Union Affairs award, Renee Hsia will spend the 2019-2020 academic year conducting research on how undocumented migrants access healthcare in Spain and Italy. She will be based at the University of Alicante. She obtained her undergraduate degree from Princeton University, Master’s of Science from the London School of Economics and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and medical degree from Harvard Medical School. She completed her residency in emergency medicine at Stanford University. She is currently Professor of Emergency Medicine and Health Policy at the University of California San Francisco.

Articles are written by Fulbright grantees and do not reflect the opinions of the Fulbright Commission, the grantees’ host institutions, or the U.S. Department of State.